On 23 September 2022, Kwasi Kwarteng staged something he called a “fiscal event”. That wording seems to have been chosen to avoid the political/economic scrutiny that would be due to a budget. Instead his measures were scrutinised by the financial markets, which reacted with a huge sell-off.

I’m going to ignore the aftermath and look at what Kwarteng and PM Liz Truss were trying to do. The fiscal event was a reduction in taxes, notably income tax. Reductions in income tax naturally benefit people who earn income, and higher earners gain most from tax reductions. This was underlined by Kwarteng’s abolition of the highest (45%) tax rate, previously levied on annual incomes of over £150 000. Truss and Kwarteng repeatedly described this as a plan for growth. And that is my concern here: does making rich people richer lead to growth?

Growth is a measure of total economic activity; an increase in the production of goods and services. The Kwarteng-Truss economic theory is that if rich people are taxed less, then they will use their increased wealth to invest in the creation of the sorts of goods and services that made them wealthy in the first place. The theory suggests that this creation of additional goods and services benefits society as a whole because the total wealth of society has increased. So there are two questions to be addressed: firstly, does dividing the pie (Truss’s phrase) in such a way that wealthier people keep a bigger share actually cause growth in overall economic activity? Secondly, does economic growth automatically benefit all sectors of society?

We should be able to answer the first question by looking at what has happened when the rich have increased their share of the pie. Where might we find such a society? Funnily enough, I found it in the House of Commons library in Brigid Francis-Devine’s 2021 report “Income inequality in the UK”.

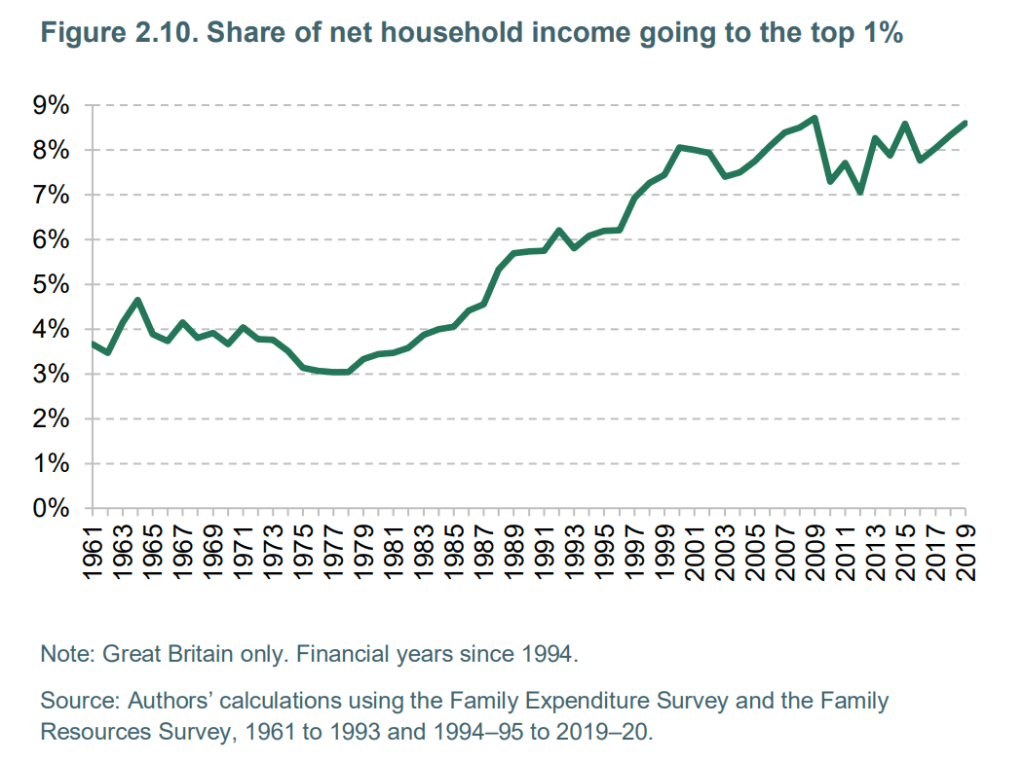

What the graph tells us is that between the mid 1970s and the present day, the top 1% of UK earners have seen their share of national income rise from about 3% to over 8%. So 1% of the earning population receives 8% of all available income.

So we already live in a society of the sort described by Truss, where wealthy people have progressively received more of society’s income. According to Kwarteng and Truss, this is a good thing. According to their theory, the more income that rich people get, the more the economy will grow. So is that true?

Here we turn to the Office for National Statistics and their publication of changes in the economy since the 1970s :-

According to Trussonomics, having a greater share of income going to the top 1% should have caused the rate of growth to increase. Instead, over the period where the top earner’s share of income has increased, growth has remained stubbornly flat (in fact a very small downward trend).

So we have demonstrated clearly that increasing the share of income going to the highest earners does not increase growth in the economy as a whole. We’ve tried that experiment: it didn’t work. If we return to the first graph for a moment, we can also see whether the average 2% growth of the past fifty years has benefited the whole of society. The fact that the richest have grabbed an increasing share suggests that they have benefited disproportionately compared to society as a whole.

So does making rich people richer lead to growth? No it does not. The Kwarteng-Truss economic theory is, at best, a load of cobblers, and very likely damaging to the economy as a whole.